Myers-Briggs Test Raises Ethical and Moral Concerns

Used by 2 million people annually, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) test is trusted by companies, colleges and even the federal government to hire and promote employees. Companies’ reliance on the system raises questions surrounding the morality of using a personality test as a deciding factor in determining job opportunities.

80% of Fortune 500 companies use personality tests for their companies, with MBTI being one of the most popular, according to Forbes. However, the public is concerned about the ethics and accuracy of the test.

The MBTI website claims its goal is to “make the insights of type theory accessible to individuals and groups,” despite the fact that the test is not based on a scientific study. Instead, the 16 personality types are based on Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung’s untested theories.

Katherine Briggs and her daughter Isabel Briggs Myers, both of whom had no experience in psychology, first created the test. The personality types they proposed were based on Jung’s ideas, which were entirely rooted in his own experiences and observations. Jung only tested his theories on family and friends, while no technical scientific experiments were conducted.

Jung himself warned that the personality types were not strict classifications: “There is no such thing as a pure extrovert or a pure introvert. Such a man would be in a lunatic asylum,” he claimed in an interview in the 1960s. Yet, MBTI tests clearly categorize people into introverts and extroverts.

Moreover, many modern-day experiments show the test is inaccurate and inconsistent. In one study, more than half the people who retook the test after five weeks got a different result. Out of the 221 studies done on the MBTI personality test, only seven met the criteria for “validity,” where the results given are generally true, or “reliability,” where most people receive the same answer if they retake the test.

Additionally, some believe the test is designed to placate the person taking it, as recipients only receive the positive traits designated to their personality type and none of the characteristics they need to improve. This makes people feel good about their results, leading to positive reviews which, in turn, draws more test-takers.

I would not apply for or accept a job that required the use of the MBTI or required me to report my Myers-Briggs type.

— Cecilia Laguarda

Furthermore, the Myers-Briggs Company makes roughly $20 million a year according to the Washington Post — to take the official MBTI personality test, individuals are required to pay $49.95. Paying this fee gives individuals access to other resources relating to MBTI personality types alongside their results. Because the Myers-Briggs Company profits from this process, some claim they do not prioritize the accuracy of the quiz, instead giving flattering but inaccurate results.

Although the Myers-Briggs Company works with psychologists, many question if the test is scientifically accurate. Despite the popularity of the MBTI test, it has rarely been published by major psychology journals, other than a few instances in which its accuracy was questioned. Carl Thoresen, a psychologist on the board for the Myers-Briggs Company, admitted to the Washington Post in 2012 that “[it] would be questioned by [his] colleagues” if he used it in his research.

The Sidwell community has varied thoughts about the test.

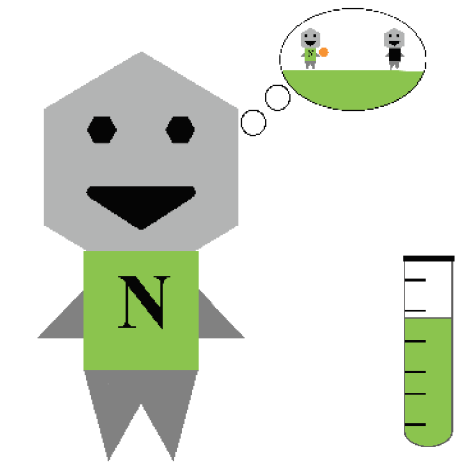

Upper School Math Teacher and Athletics Coach Jon Mormino said the MBTI test is a “legitimate small component for an employer to consider,” but that it would be unfair to solely hire people based on their MBTI test results without at least an interview. In the past, Mormino has found the MBTI test to be consistently accurate: the first time he took the test, he was categorized as an INFP; more recently, he was categorized as an INFJ, a difference of only one trait. Overall, Mormino claims he is not opposed to the use of MBTI tests for job opportunities, as long as there are other factors in consideration — he would be open to taking a personality test if needed for a future job.

Unlike Mormino, Upper School Human Behavior and History Teacher Joshua Small is against using the MBTI test for job applications. He took the test for an evaluation of employees at a past school before coming to Sidwell. Small said that many of the traits he received were inaccurate and “against any kind of standardized objective score” of people’s personalities.

Biology teacher Cecilia Laguarda is another strong believer that the MBTI test should not be used for job applications. “The Myers-Briggs test should not be used in places of employment except on a voluntary basis,” she said. “I would not apply for or accept a job that required the use of the MBTI or required me to report my Myers-Briggs type,” she continued.

In fact, the Myers & Briggs Foundation agrees with Laguarda and Small’s views on the ethics of using the MBTI test for job opportunities. According to the Myers & Briggs Foundation’s website, “[it] is not ethical to use the MBTI for hiring or for deciding job assignments.”

If even the foundation questions the test’s ethics, companies should rethink if it is appropriate to use the test in the workplace.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Sidwell Friends School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Emma Canan is currently a News Editor for Horizon. Prior to this, she worked as a Staff Writer for the newspaper.

Quinn Patwardhan is currently Graphics Editor for Horizon, a position he held in the 2022-2023 and 2023-2024 school years.