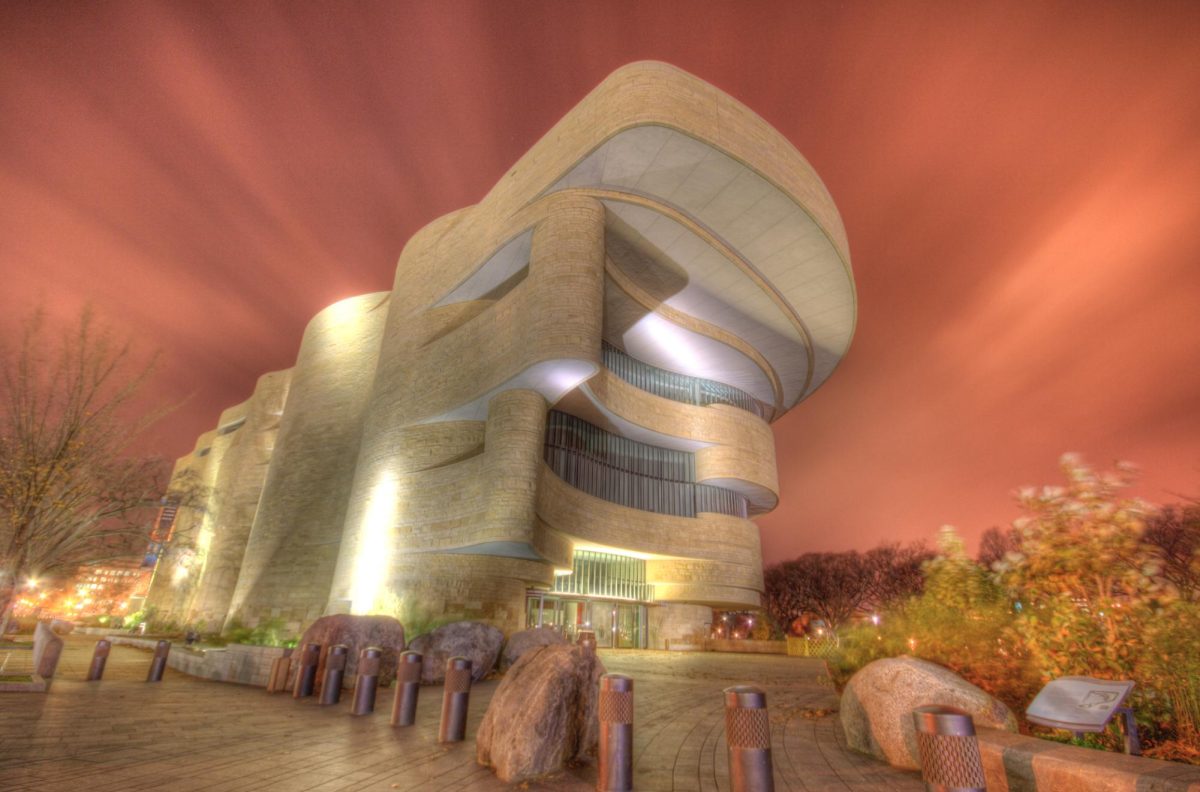

“Return to a Native Place: Algonquian Peoples of the Chesapeake” has been a long-standing gallery display and a staple exhibit at the National Museum of the American Indian. Through maps, ceremonial objects, photographs and interactive displays, the exhibit aims to provide deeper insight into Native American culture.

Curated by Gabrielle Tayac of the Piscataway Tribe, nearly since the opening of the museum, the exhibit covers the Native American tribes of the Chesapeake area, encompassing what now includes Washington, Maryland, Virginia and Delaware. It aims to provide a comprehensive history and timeline while spreading awareness of what the tribes of the area have not only experienced, but persisted through until today.

Located on floor two of the museum, the exhibit begins with a quotation from a Patuxent man to the Governor of Maryland, Leonard Calvert, in 1634: “You should rather conforme your selves to the customs of our country, then impose yours upon us.” Visitors are introduced to the Nanticoke, Piscataway and Powhatan tribes of the Chesapeake, followed by a quote from Tayac: “archaeologists say that Indians have lived here for more than 11,000 years. Nanticoke, Piscataway and Powhatan people say that we’ve been here forever,” reminding exhibit visitors of the often unrecognized extent to the land’s history.

Following the introduction, the exhibit describes the initial encounters with the Europeans before most tribes and the difficulties that followed in the section titled “Dark Days in the Chesapeake: Broken Treaties and Overrun Reservations,” a nod to the “Dark Days,” a name the Piscataway gave to the era.

While the English initially relied on these Indian tribes in the 1600s for survival in fledgling colonies such as Jamestown, the same colonists would ultimately turn against them in the several Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1610-1646) and Bacon’s Rebellion (1676).

These broken treaties left the Algonquians with a sizable portion of their territory taken over or stolen, their population ravaged and broken and the constant looming threat of further extortion.

The section “Knowing the Earth: Chesapeake Native Identities” explains the rich ideologies and lifestyles of the Native peoples of the Chesapeake as they cultivated and promoted an attachment to the ways of nature through a deity known as the Creator.

The Natives of the Chesapeake believed the Creator brought them here and, through careful instruction, gave them the benefits of nature while agreeing to care for and watch over the natural world. In a land with an abundance of water, Natives relied on seafood such as oysters, crabs and rockfish, which pervaded the area, viewing the water as a spiritual gateway to trade and travel to their ancestors.

The exhibit continues into the “Revival” section, describing the Indigenous experience during the 20th century after a period of assimilation. While many attempted to bring about a cultural revival during the early 1900s through forming political rights associations and formal tribal schools, ambivalence and fear towards potential white retaliation dampened their progress.

During the late 1960s, however, the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the concurrent rise of the American Indian Movement in the later 1960s sparked greater change. Leaders from Chesapeake tribes and communities joined the Coalition of Eastern Native Americans, regaining government structure and recognition. In the 1980s, Virginia officially recognized the Powhatan and Monacan Nation as official tribes.

While the exhibit underscores the devastating plight of the Native peoples of the Chesapeake, it illuminates these communities’ persistence, which has allowed them to best preserve their structures, cultures and selves up to the modern day.