Upper School Chinese Teacher and Assistant Dean of Students Xuan Wang never thought teaching would be her career. Her path to becoming a teacher began with the college admissions process.

Wang applied to East China Normal University (ECNU), a renowned teachers college in Shanghai, expecting she would not get in. Although she was more interested in STEM, she indicated finance and international Chinese studies as top majors because they had been the most popular among admitted students from her province.

Wang was ultimately accepted to ECNU as an international Chinese studies major, selecting the translation track. “Up till that point, I didn’t know that I’m going to be a teacher,” Wang said. “But then, when you are with a school that’s a teachers college, your internships and opportunities are most likely related to education, so even though I never thought about teaching, I started tutoring in sophomore year.”

Wang enjoyed supporting students one-on-one and connecting with them; the “very special relationship” she developed with the first family she worked with lasted throughout her college years. However, she still did not plan on becoming a teacher.

Wang described her third and fourth years in college as a “period of confusion.” While other students were “trying to find jobs, internships,” and other opportunities, Wang “didn’t know what to do.” She decided to continue her education and earn a master’s degree.

Wang’s first year of graduate school in China was a turning point for her. In 2007, the University of Virginia’s Chinese Language Program — an eight-week immersion program in Shanghai — partnered with her university in search of teacher trainees. Wang applied, thinking that her previous experience tutoring would help her succeed in the role.

Once she was accepted to the program, professor Hsin-Hsin Liang, who Wang described as “very passionate, very experienced and a great mentor,” instructed Wang and the other trainees in teaching Chinese as a foreign language.

“At that point, I realized that teaching Chinese is not like, you’re Chinese, you can teach Chinese. It’s not like that. There’s a lot of best practices, theories, ways, that’s been proven successful to teach,” Wang said. She was also struck by the intensity of the program: “You’re basically 24/7. The whole eight weeks, you’re with the kids, except when you go back to the dorm and sleep.”

Soon after that, Wang began studying for a master’s degree in foreign language education at New York University. When she came to New York, she expected to stay only for the one-year duration of the program. After the 2008 financial crisis, however, she remained in America, eventually moving to Fairfax County, Va., where her husband became the youngest person ever to serve on the school board.

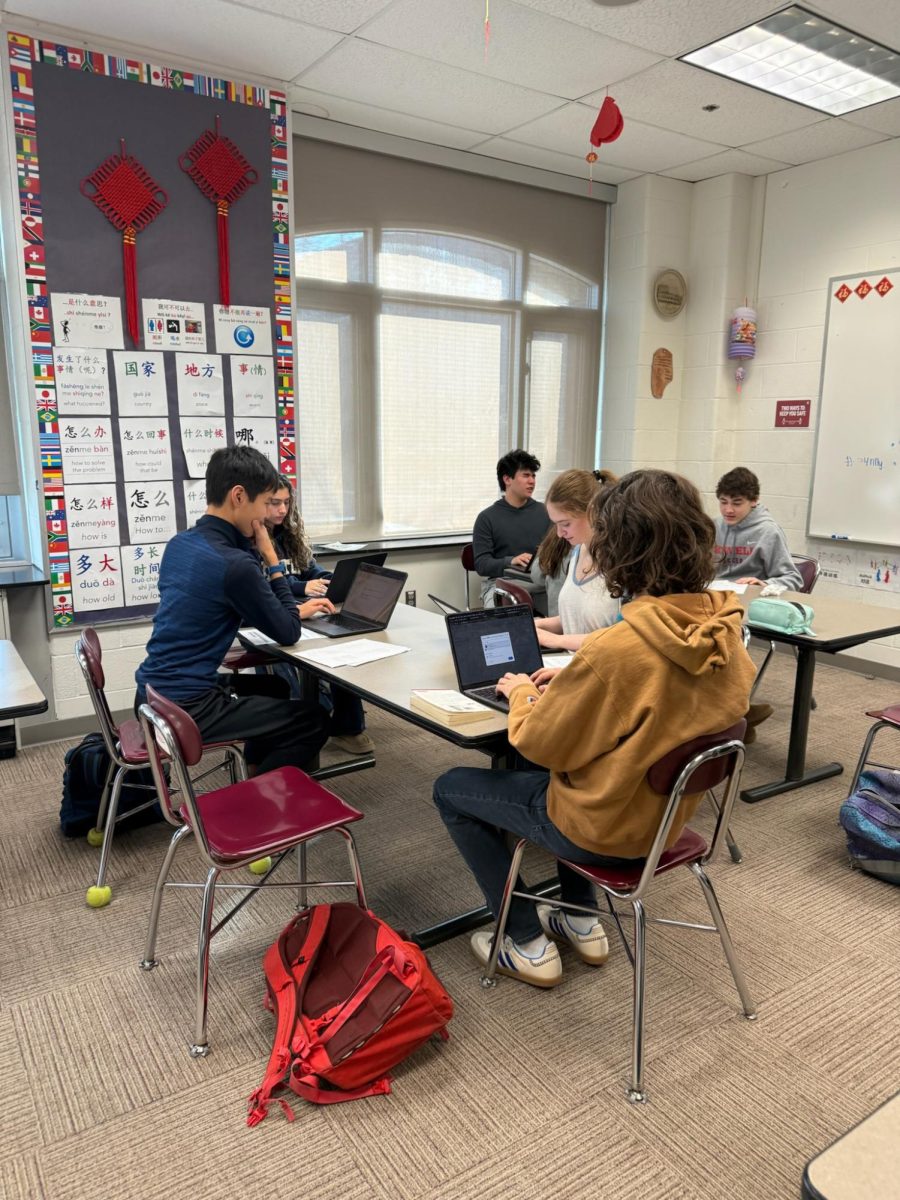

In 2012, Wang began teaching at Sidwell Friends School. That year, she also worked as the assistant coach of the volleyball team. Before that experience, Wang had “no idea” of the sports commitment at Sidwell. Coaching volleyball gave her “a totally different understanding” of how to teach, leading her to adjust her lessons. Wang now plans to help coach cross country this fall.

Another challenge Wang faced at Sidwell was teaching without a textbook, which meant “giv[ing] up 90 percent” of what Wang had been taught before and learning a whole new system. However, Wang took this new situation positively, relating it to the Chinese saying bùpò-bùlì, which means that construction is impossible without destruction.

To Wang, the most important part of teaching is the relationship she forms with her students. “In the end, teaching is about building that kind of meaningful relationship with the student,” she said.