Every summer, deep in the Nevada desert, a community gathers to celebrate Burning Man, a festival renowned for its art and titular “Burning Man.” This year, the festival was made memorable by the extreme weather that trapped its participants for several days in ankle-deep mud. Attendees were told to conserve food, water and fuel and to find shelter in the Black Rock Desert as the entrance was closed, leaving them stranded.

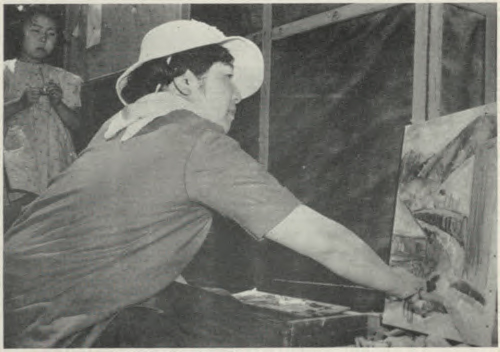

According to their website, the Burning Man festival is “dedicated to community, art, self-expression, and participation.” Every summer, Burning Man’s participants, known as “burners,” build Black Rock City, a ramshackle combination of a trailer encampment and futuristic art exhibits, on the Black Rock desert. They create towering, ambitious works of art that rise, surreal, from the desert’s haze. This year, standouts included an inflatable pink tiger, a bridge of birds and a stained-glass structure. Visitors rode around the campsite in winged jeeps, Trojan horses and wheeled pirate ships.

One of the ten principles of Burning Man is gifting, and another is decommodification; transactions do not occur within the ephemeral city. At the end of the festival, once a giant sculpture of the Man is incinerated, participants dismantle the city, leaving no trace.

While northwest Nevada — where the festival happens — is typically known as a dry area, this year, according to The New York Times, it was a “rain-gorged stew of mud and slop.” This drastic shift in weather patterns is part of a recent trend of extreme weather events related to global warming. Although the area started clearing up on Monday, around half of the attendees left as soon as possible. 50-year-old attendee Kristine Rae, who left on Monday, reported to The New York Times that she saw people who encountered deep puddles and that there were “cars stuck halfway up their wheels.”

The rain turned the dust into a thick, sticky mud that closed down roads and encrusted toilets. With only four-wheel drives allowed to exit, many burners trekked miles through the mud to reach the nearest highway. Many more hunkered down for days, their food running low. The rain continued, surprising Patrick Donnelly, the Great Basin director at the Center for Biological Diversity; according to Donnelly, “There’s always been monsoonal activity and passing thunderstorms in the area. But what’s unusual is for a slow moving storm to park overhead and dump a whole inch of rain at once, like it did over the [Playa].”

The flooding demoralized many burners, leading them to reconsider returning to the festival. As Cory Doctorow, a Burning Man attendee for several years, wrote in The New York Times, “it’s hard enough to prepare for all of the contingencies of a hot, dry desert. Throw in water and mud and the contingencies multiply into towering, demoralizing heaps.” Doctorow “can see Burning Man… headed for the climate emergency’s cliff edge.”

However, some attendees embraced the change by finding the positive side of the new conditions. According to The New York Times, attendee Donovan McGrath said, “There were many silver linings. The rain provided an amazing opportunity to walk, to move more slowly, to connect with people you may not have.”