“Pictures of Belonging,” a new exhibit at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, showcases the story of Japanese-American internment during World War II through a new lens.

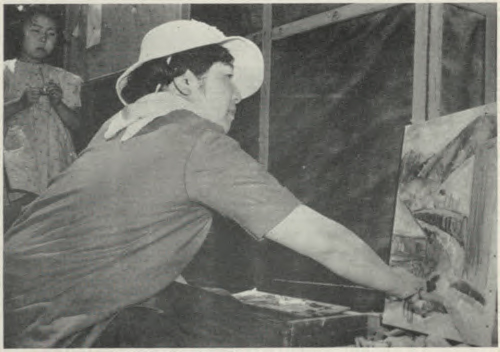

Curated by Art Historian Dr. ShiPu Wang, the exhibition focuses on three artists: Hisako Hibi, Miné Okubo and Miki Hayakawa. Each of the women lived in the San Francisco Bay Area before World War II, and were already prominent artists. During the war, Hibi and Okubo were sent by the Tanforan Assembly Center to the Central Utah Relocation Center, known as Topaz, while Hayakawa moved to New Mexico to avoid incarceration.

In an interview with UC Merced, Wang described how “the exhibition thematically and chronologically charts the artists’ sustained engagement with and contributions to various artistic, cultural and sociopolitical movements” through a variety of different styles.

Hibi was initially imprisoned in the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno and later moved to Topaz. Most of her works during and after her incarceration feature the Topaz’s blocky, gray buildings. Her style is impressionist, with a soft focus and blurred lines. Her paintings from the camp are more muted than her earlier work, replacing warm colors with grays and browns. Still, several of her works show brilliant red sunsets over Topaz, evoking the destructive beauty of a volcano, while the rigid gray buildings fade in the background against the vivid sunset.

Other scenes from Topaz contrast the desolate camp with the surrounding nature. For example, “Topaz Flower” shows a brilliant yellow flower against a brown background and a cold gray table. The flower’s curves contrast with the sharp lines of the table. The Washington Post described Hibi’s landscapes as “convey[ing] the paradox of confinement amid the vast terrain beyond the camp walls.”

Hibi alternates between realism and surrealism, present in her work “Frightful New York.” She mostly casts her portraits in browns, reds and greens, capturing people in the midst of their lives, but in “Frightful New York,” Hibi paints in shades of gray and black. The only pop of color is a woman in a bright pink dress positioned in the foreground. A skeleton horse draws a cart laden with produce, the only other source of color in the piece.

After the war, Hibi began exploring abstract art. By the 1980s, her works were mostly abstract, with shapes rising out of neutral backgrounds, vast sweeps of color, bright light sources, kanji scattered across the paper and faint sketches of people and shapes.

Okuba, who was also imprisoned in the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno and then moved to Topaz, has a very different style than Hibi. Before and during her incarceration, Okuba drew her technique from magazines and advertisements. Her landscapes have an almost childlike quality, featuring bright colors and blocky, thick lines, while her portraits show flat, stylized bodies inspired by the early Renaissance and Mexican muralism. Okuba often sketched the everyday life of people in the camps, especially focusing on children. According to The Washington Post, her sketches are the foundation of a graphic memoir, “Citizen 13660,” documenting life in the camps.

Okuba’s art even led to her release — after she helped establish a camp magazine, she landed a job as an illustrator for Fortune magazine. That position allowed her to leave the camp and move to New York. After her release from Topaz, Okuba began exploring cubism, and her color palette drifted more toward blacks, reds and pinks. By the 1980s, her works focused on simplified geometry.

Although never incarcerated, Hayakawa was still forced to relocate. Of the three artists, her work utilizes realism the most, especially in depicting the natural world. While her landscapes use greens and browns, her portraits are much darker. Hayakawa’s paintings also have a sharper focus and crisper lines than the other artists’ works.

Several portraits of women in the exhibition diverge from her usual style; they seem less detailed, almost unfinished. Their faces carry much more depth than the rest of the image, and their figures are more curved than Hayakawa’s other subjects.

The Washington Post described Hayakawa’s earlier portraits as “sumptuously fleshy, serious and still, with an almost ethereal light that emanates from her subjects.” Her later portraits became more ethereal and softer, focusing on evoking the true nature of the individual.

Though the three artists have distinct art styles, each shows a different side of World War II and the effects of the Japanese internment camps. Wang explained to UC Merced that “‘Pictures of Belonging’ invites the viewer to not only appreciate and learn about these artists’ work but also reflect on what (and who) defines American art in specific historical moments, while examining reasons for the omission of these artists from accounts and museum collections of 20th-century art in the United States.”

The exhibition is currently on display at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. It will remain there through Aug. 7. It will then be displayed at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, the Monterey Museum of Art and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.