Since the school’s founding, Sidwell students have engaged in activism on key political issues, leading protests and targeting difficult conversations. Ranging from recent demonstrations, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, to activism on historical topics such as apartheid, these demonstrations have helped students engage with critical issues over the years and spotlighted diverse opinions within the Sidwell community.

________________________________________________________________________________

Apartheid

Between 1948 and the early 1990s, apartheid — a system of racial segregation in which the white majority held disproportionate power and land — shaped the South African social sphere. The system, which was met with significant criticism by international actors, inspired Sidwell students to form the Student Coalition to Combat Apartheid (SCCA).

“Our goals were ambitious and clear: to educate high school students about the evils of apartheid, to petition private schools to divest from South Africa, to work toward the release of Nelson Mandela and all political prisoners, and to redirect media attention to the plight of the vast South African majority in their struggle for freedom,” said Alexander Levering Kern ’89, who spearheaded the initiative.

However, some Sidwell students did not care for the SCCA’s approach. In the November Horizon issue, a letter sent to the editors by Sidwell student Masaki Hidaka was also published. In this letter, Hidaka was highly critical of a recent publication by the SCCA in which they published a graph categorizing individuals as “White, African, Colored, and Indian/Oriental.”

“First of all, what is Colored? Anything darker than white and not African? And why are Indians grouped with Asians?” Hidaka asked. “They are two totally different races from two totally different countries. The members of the SCCA, an organization created to fight racism, are practicing it themselves.”

“I personally think the formation of a student coalition to combat apartheid is a noble idea,” Hidaka said. “[B]ut if the SCCA is going to step on other racial problems to cure its own, it should be dismantled.”

________________________________________________________________________________

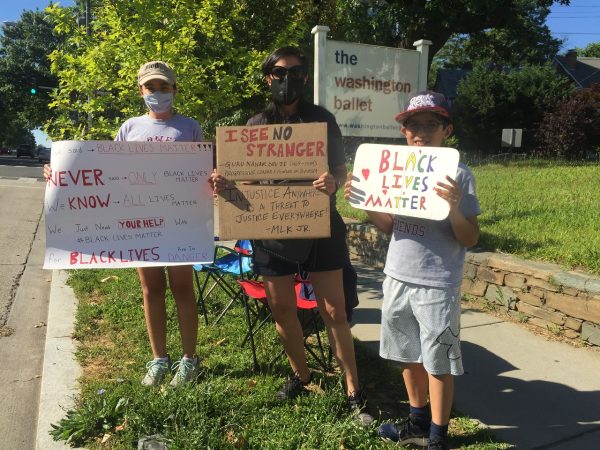

Black Lives Matter

On June 13, 2020, Earnest Williams ’20, then a senior at Sidwell Friends, spearheaded a student-led Black Lives Matter march in Washington. Williams organized the protest in the midst of COVID-19, and only after creating “a solid plan” did he realize the obstacles the pandemic and social-distancing requirements posed.

However, after calling government departments and officials, Williams and fellow organizers were informed that, as long as they were aware of the pandemic, they had their First Amendment right to free speech. So, students returned to the drawing board and continued planning.

The protest, which Williams described as “an absolute win,” began at Fort Reno Park, where guest speakers “spoke to the crowd about cultural appropriation and racial inequity” and celebrated the rich and vibrant Black culture through poetry, according to the August 2020 Horizon issue. Students led the group in marching to the National Cathedral, where they “knelt in solidarity and silence for Black lives.”

Williams, who graduated from Sidwell that June, felt confident the student body would continue creating spaces for activism and protest: “500+ beyond capable people walk through those Sidwell halls.”

________________________________________________________________________________

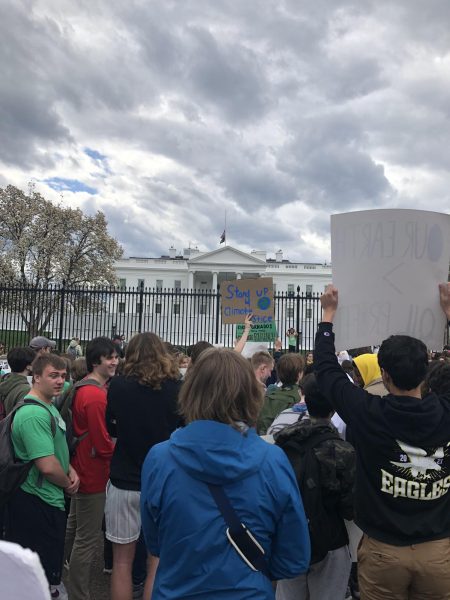

Environmental Activism

On Sept. 20, 2019, thousands of students in the Washington area left school and gathered outside the Capitol as part of the Global Climate Strike, joining millions across more than 150 countries.

When a group of Sidwell Friends middle schoolers realized they were unable to join the strike downtown, they decided to bring the protest to campus instead. Dozens of students gathered in front of Zartman House during their break to chant and wave signs.

“We were out on Wisconsin and everyone was honking,” senior Gabi Green said. “That was in sixth grade.”

For some students, their involvement in environmental activism began even earlier. Senior Isabelle Reinecke, a head of the Friends Environmental Action Team (FEAT), planted a tree with her neighbors when she was just four.

“They were kind of obsessed that a four-year-old was there, so they named the tree after me,” Reinecke said. “That kind of sparked my whole interest in tree planting and forest health.”

By second grade, Reinecke had given up plastic and began encouraging others to do the same. In middle school, she launched Youth Against Plastic Pollution, a nonprofit focused on reducing everyday plastic use, and joined the middle school’s FEAT.

“In ninth grade, some people in the Upper School already knew about my environmental work, and they pushed me and empowered me to be really involved with Upper School FEAT,” Reinecke explained. “They had me leading groups to go to these protests even though I was just a freshman.”

In her sophomore year, Reinecke became a lead regional organizer for Fridays for Future DC, Washington’s chapter of the international youth-led movement founded by Greta Thunberg, which encourages students to skip Friday classes to participate in climate strikes.

“It takes a shocking amount of work to organize a protest. I think those ones I organized in 10th and 11th grade were especially special, because it’s just so cool to see all of that work you’ve done … you have hundreds of people there, and you’re leading them in chants. It’s the craziest feeling,” Reinecke said.

However, activism came with its challenges. Reinecke felt that there was constant pressure to be “perfect” and “know the ins and outs of every single political issue” or risk being judged. “I’m always trying to be as informed as I can, but no one can know everything about everything,” she said.

By the end of her junior year, Reinecke decided to step back from organizing protests because of the toxic culture surrounding activism. However, she remains inspired by the broader culture of student activism at Sidwell.

“It’s been meaningful to see the energy, and how excited Sidwell students are about going to protests,” she said. “Everyone gets involved in such unique ways, and has their own little niche in environmental activism, or whatever activism they’re engaged in, and I find that really interesting.”

________________________________________________________________________________

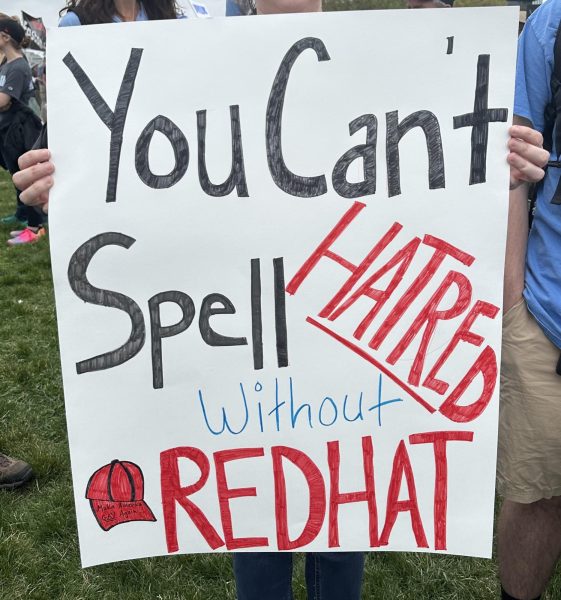

Women’s March

On Jan. 21, 2017, hundreds of thousands gathered in Washington for the Women’s March, a worldwide protest held the day after President Donald Trump’s first inauguration. At the time, the march was the largest single-day protest in United States history.

Sidwell’s Female Empowerment Club (FEM) organized a meet-up for members of the school community attending the march, including students, faculty and family members.

“As soon as I heard about the Women’s March, I knew I wanted to be a part of it,” said Hannah Coffin ’17, who was a FEM head during her time at Sidwell. “From early on in its planning it was obvious that the march was going to be a massive event, and I felt a responsibility to show up for myself and my community.”

According to Coffin, the march offered an opportunity for students to take action and “build stronger bonds with each other for comfort and protection.”

“Although it was a long and tiring day of standing and fighting for elbow room in the massive crowd, I remember feeling empowered by how many people had showed up because they shared a fundamental belief in equality,” Coffin said.

Coffin recalled the extensive debate leading up to the march on whether participation was driven by “truly intersectional goals.” However, she found that the large attendance proved “we didn’t all need to be perfectly aligned to be a part of the same movement. It was enough to believe in each other’s rights and want to move in the right direction together.”

Coffin found that Sidwell is “very engaged in activist movements,” not only through specific events such as the Women’s March but as a part of students’ everyday learning. She appreciated how the fundamental values of Quakerism translated clearly to involvement and activism. “I was learning alongside people who also wanted to make the world a better place,” she said.

Even years after graduating, Coffin’s experience at Sidwell continues to shape her approach to activism. “I went on from Sidwell to join more communities and discover different types of activism, but the lessons I learned and people I knew in high school were some of the most impactful to building my values and beliefs,” she said.

“Don’t forget to focus on the good things you want to bring about in the world rather than the bad things that scare you,” Coffin advised students. “Being an activist can be exhausting and frustrating, but when you’re doing it with the right people and for the right reasons, it should be fun too.”

________________________________________________________________________________

Hands Off Protests

In April, millions of Americans took to the streets as part of the Hands Off protests, a series of nationwide demonstrations against numerous Trump administration policies.

Senior and protest attendee Gabi Green found herself surprised by how little social media focused on the protest. Green, who heard about the protest through word-of-mouth, believes the current administration’s fear-mongering tactics contributed to the lack of coverage and transparency of the event. “I don’t think [the organizers] were actually prepared for the amount of people that were there,” said Green.

Green decided to participate in the protest because “if my kids ask me what I did, I need to tell them that I actually went out and tried to make a difference.”

However, many were afraid to join the march, and major news outlets largely avoided covering the protests. According to The Guardian, “If you picked up a major print newspaper the next day? You’d barely know it happened. The New York Times relegated the protests to an image below the fold with a caption instructing readers to turn to page 18 for more information.”

“On the front page of the Washington Post, it was under the fold,” Green said. “Even the Washington Post [and other media outlets] is dying down, which I think is beyond dangerous.”

Like others, Green found herself afraid to post about it on social media. While in past marches, people have posted, Green noticed that as she scrolled through her Instagram feed, “no one was posting.”

“The way they’re [MAGA supporters] able to access our data is so dangerous … fear is the tactic in this administration, which is why it’s hard to stand up and hard to blame people for not taking a stand,” Green said, who believes the whole DMV area has been stunned into silence.

“This is the first time in my life that I’ve actually been scared to use my First Amendment right to free speech,” Green said. “Even publishing something like this [article] feels risky. For the first time ever, you feel scared to speak up.”