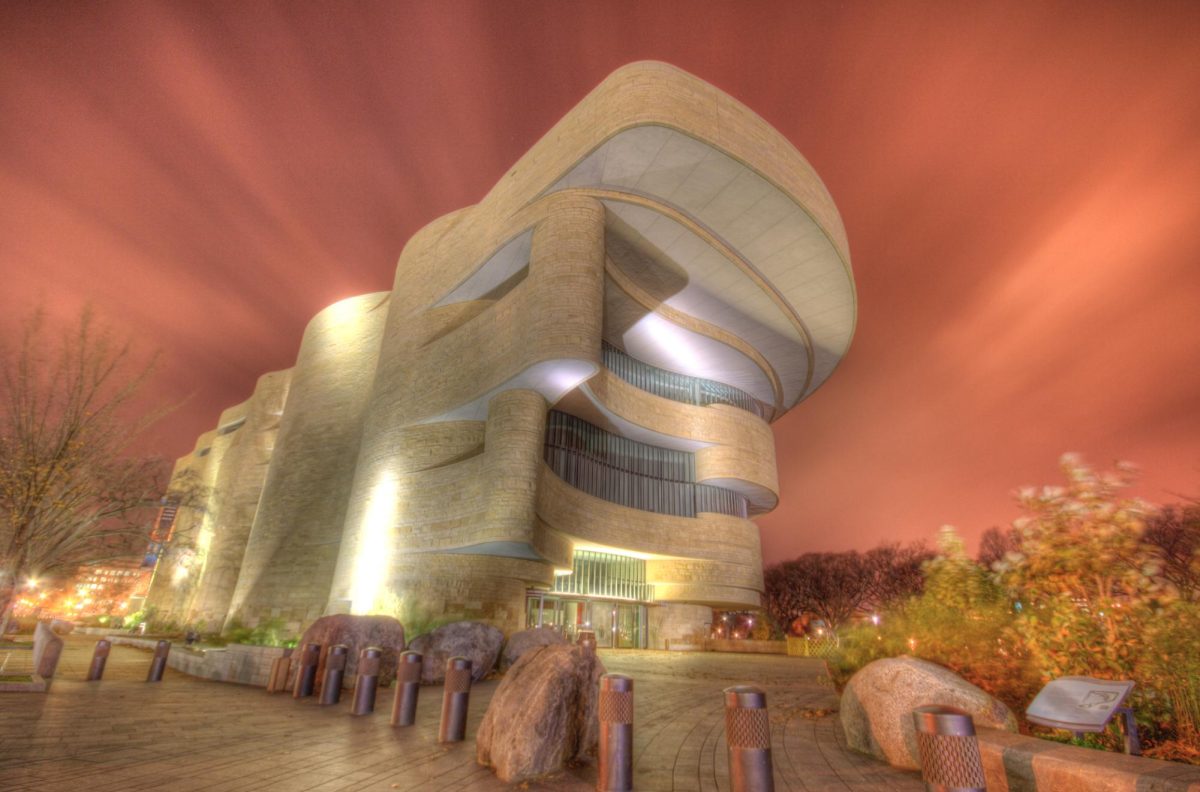

I’ve never seen the man in the photograph before, but I already feel like I know him. Looking at pictures in the National Gallery of Art’s exhibit, “Gordon Parks: Camera Portraits from the Corcoran Collection,” I’m struck by how precisely and intimately Parks, the late photographer and composer, captured his subjects.

Parks, born in Fort Scott, Kan., in 1912, faced segregation, oppression and loss in his childhood. When he was sixteen, his mother died, so he left home and worked as a railway porter until he bought his first camera.

He began working as a photographer in Chicago where he became a member of the art scene at the South Side Community Art Center, befriending luminaries such as Langston Hughes, with whom he hoped to create an exhibition juxtaposing their art to express African Americans’ experiences. The exhibition never came to fruition, but Parks’s portrait of his friend posing beside a frame, empty except for Hughes’s raised hand, is a tantalizing glimpse of what could have been.

After working as a photographer for the government, Standard Oil Company, Vogue, Glamour and Ebony, Parks became the first Black photographer for the magazine Life. His period working there was fruitful. At Life, Parks was able to express his artistic philosophy, photographing his subjects where they worked and lived to better “[address] their cultural significance” and familiarizing himself with their tics and “gestures.”

His philosophy is especially evident in two pictures he took while reporting on Muhammad Ali. In the first, Ali, soaked in sweat from training, stares into the distance contemplatively. In the second photograph, Ali poses in a suit, looking downwards.

Journalism allowed Parks to travel the world. In Latin America, he photographed extreme poverty. Parks’s poignant photo of 12-year-old Flavio da Silva, who had to provide for his seven younger siblings despite his severe asthma, inspired Life readers to donate enough money to bring da Silva to America for medical care.

Parks’s reporting also connected him to some of the most influential activists and artists of his era, from Malcolm X, who he photographed at a rally in Chicago, to Duke Ellington, Leonard Bernstein, and Alexander Calder. Parks’s portraits of Ellington and Calder are masterful. In Ellington’s portrait, Ellington sits at a grand piano listening to playback of a record he is working on as his face is reflected in the piano lid. There’s an eerie and spiritual quality to Calder’s portrait, where Calder’s illuminated hand, reaching out to set a shining mobile in motion, is the only part of his body visible in the darkness.

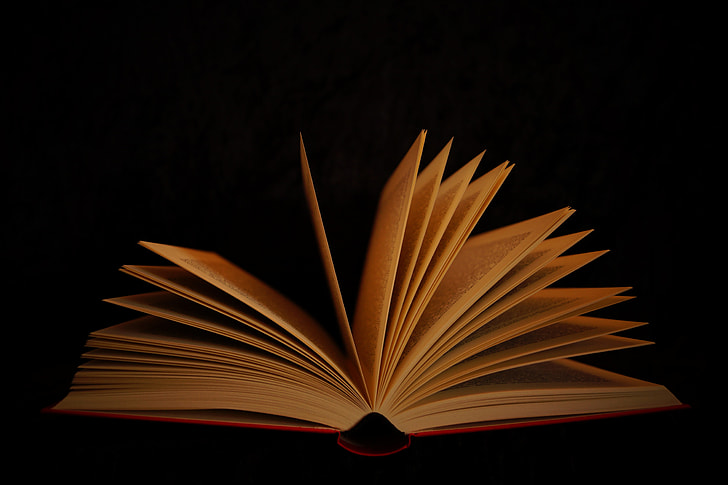

In addition to photographing celebrities, Parks captured images of his friends and neighbors. In his portrait of Pauline Terry, an old friend from junior high school, and her husband Bert Collins, taken in 1950, Collins stares warmly at the camera, a cigar dangling from his lips and a worn Bible in his hand, while Terry seems more reserved and melancholy. Another portrait, of Mrs. Jefferson, whom he knew as a child in Fort Scott, is regal. Jefferson, who was 98 years old when the picture was taken, exudes grace, strength, and wisdom.

To make an artistic portrait is to attempt to capture the essence of a person—in their posture, in their expression, in their pursuits. Through his honing of his craft, his respect for his subjects, and his creativity, Gordon Parks attempted this and succeeded.

“Gordon Parks: Camera Portraits from the Corcoran Collection” is on display until Jan. 12, 2025, at the National Gallery of Art.