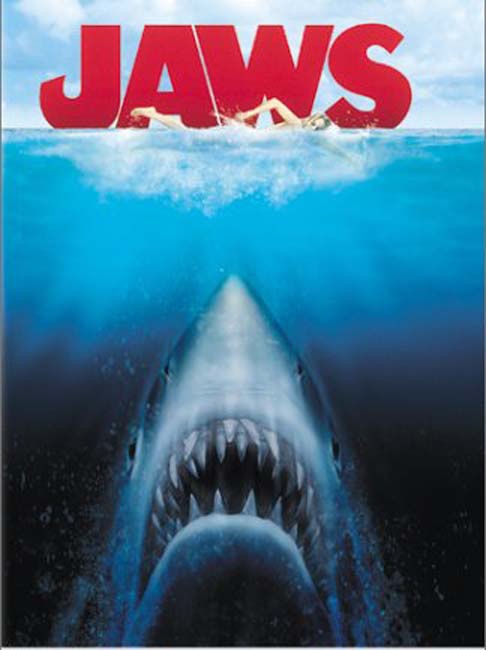

There’s a reason why I and many others call July 4 “Jaws Day.” The excitement is palpable throughout the month — Amazon Prime rents the film for four cents, it reappears in cinemas nationwide, and Google searches for the USS Indianapolis disaster skyrocket. Americans are simple: When the fictional anniversary of the night Brody, Hooper and Quint defeated a bloodthirsty shark rolls around, we can’t get enough of it. Aside from Jaws Day, however, the Spielberg classic’s influence extends in ways you may have never recognized. Not only did it invent the summer blockbuster, but its popularity is to blame for why we all still shudder at the thought of swimming in the ocean. This begs a simple question: In today’s fast-paced world, how has “Jaws,” now approaching its fiftieth anniversary, maintained its cultural relevance?

For a film riddled with so many production mishaps, it’s a miracle that “Jaws” even reached theaters. Shooting on the water was no easy feat, and weather setbacks continually tripled the shooting schedule; Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw, both in starring roles, were constantly quarreling; and, perhaps most famously, the $500,000-a-piece animatronic sharks were perpetually broken, receiving only four meager minutes of screentime. Spielberg himself called the experience “horrendous,” and in his defense, it’s hard not to when you’re directing a film whose budget balloons by millions for every thunderstorm.

The beauty of “Jaws,” however, is that it turns its curses into blessings. The film could have replicated the formula of any old slasher flick, but Spielberg and crew were required to get creative with its star in constant disrepair. For instance, rather than show the shark on-screen, much of its presence is depicted through clever camera shots from its “point of view” as it menacingly maneuvers between crowds of swimmers. When it finally attacks, it vanishes entirely — solely visible is its helpless victim thrashing in the water, leaving your brain to conjure up horror stories of what exactly the creature is doing to make it scream like that. This sort of fabricated horror is what makes “Jaws” particularly scary; it preys on your fear of the unknown, an impressive, iconizing feat that would’ve been unattainable with a functioning animatronic.

Heated crew tensions, too, service the film’s remarkability despite every reason to sour it. On-set arguments are known to wreck productions, but the feud between Richard Dreyfuss and Robert Shaw, actors for Hooper and Quint, instead bolstered their performances by giving rise to an air of authenticity. Both men began hating each other around the same time their characters did, and for identical reasons: Shaw thought Dreyfuss lacked field experience. Dreyfuss thought Shaw was a commandeering bully — in his words, an “evil troll.” Their on-screen arguments share a similar bite; they angrily snap at each other, fight for dominance, and mock each other behind their backs, with their emotions lending a raw believability to their mannerisms. Roy Scheider, who plays protagonist Chief Brody, saw similar benefits, assuming his true-to-life role as the middle-man caught in the crossfires of vitriol. To this day, “Jaws” is often viewed as a masterclass of character acting. Although its stars are renowned in their own rights, there’s no doubt that the troublesome filming conditions turned their terrific performances into timeless ones.

The nightmares “Jaws” faced ended up making it better than ever. Unique in nature, impressive in scale and astounding in its actors’ prowess, the film became a breakout hit; it is now remembered as the first summer blockbuster, raking in a record-breaking $470 million, and is still studied today in collegiate-level classes for its excellence in storytelling. Aside from the professional fallout, though, you, the average reader, likely recognize it for its indelible cultural mark on sharks as we know them.

When you look at a picture of a shark, do the musical notes “E” and “F” play in your head? Do you hesitate before swimming in the ocean? If you answered yes to either of those questions, you’re likely aware that sharks earned a particularly nasty reputation after “Jaws” invented and killed the most famous one. The film approaches its villain like it would a serial killer; it’s cunning, ruthless and incorrigibly homicidal, as Chief Brody explains in a glaringly pseudoscientific monologue. With sharks — particularly great whites — understudied mainly at the time, filmgoers didn’t know any better than to take “Jaws” as gospel, leading to a colossal shark mania with consequences that echo today. Since the 1970s, shark fisheries have exploded in number, populations have declined by a staggering 70 percent, and the beach has become a source of fear rather than relaxation. Of course, we now know that sharks lack the mental capacity to carry out the events of “Jaws,” but it’s too late; you, your mother and everyone you know is already too scared to go in the water.

Peter Benchley, the author of the novel “Jaws” adapted, was famously heartbroken by the film’s consequences and spent his final days as a shark conservationist. “I couldn’t write Jaws today,” he said in an interview. Spielberg, too, told the BBC, “To this day, I regret the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film. I really, truly regret that.”

What, then, is the legacy of “Jaws?” Is it a masterpiece or troubled spectacle eclipsed by its catastrophic effects on hundreds of shark species? I’d call it a mixture of both. It’s impossible to deny that the film practically oozes artistry — it sits comfortably among the American Film Institute’s “Greatest of All Time” — but perhaps it arrived in an era that wasn’t ready for it. Media literacy is already a dying art, and “Jaws” puts it to the ultimate test, assuming that audiences will interpret it solely as what it is: A really good movie. Then again, if a movie owns the entire Fourth of July, it must be beyond “really good.”

If you’re looking for something to remember “Jaws” for, let it simply be its brilliance. Maybe your heart races as the shark sifts through victims like a pack of Skittles, or perhaps Quint, Hooper and Brody merrily singing together the night before their final battle fills you with warm, fuzzy feelings. You could even be like me and the millions who rewatch it every July, laughing with your friends and reciting the Indianapolis monologue from memory. For better or for worse, “Jaws” has left an imprint on film and ichthyological history, and it’s here to stay. That being said, may our opinions of its villain remain a thing of the past.

“Jaws” is available to stream across several services and in select theaters throughout the year.