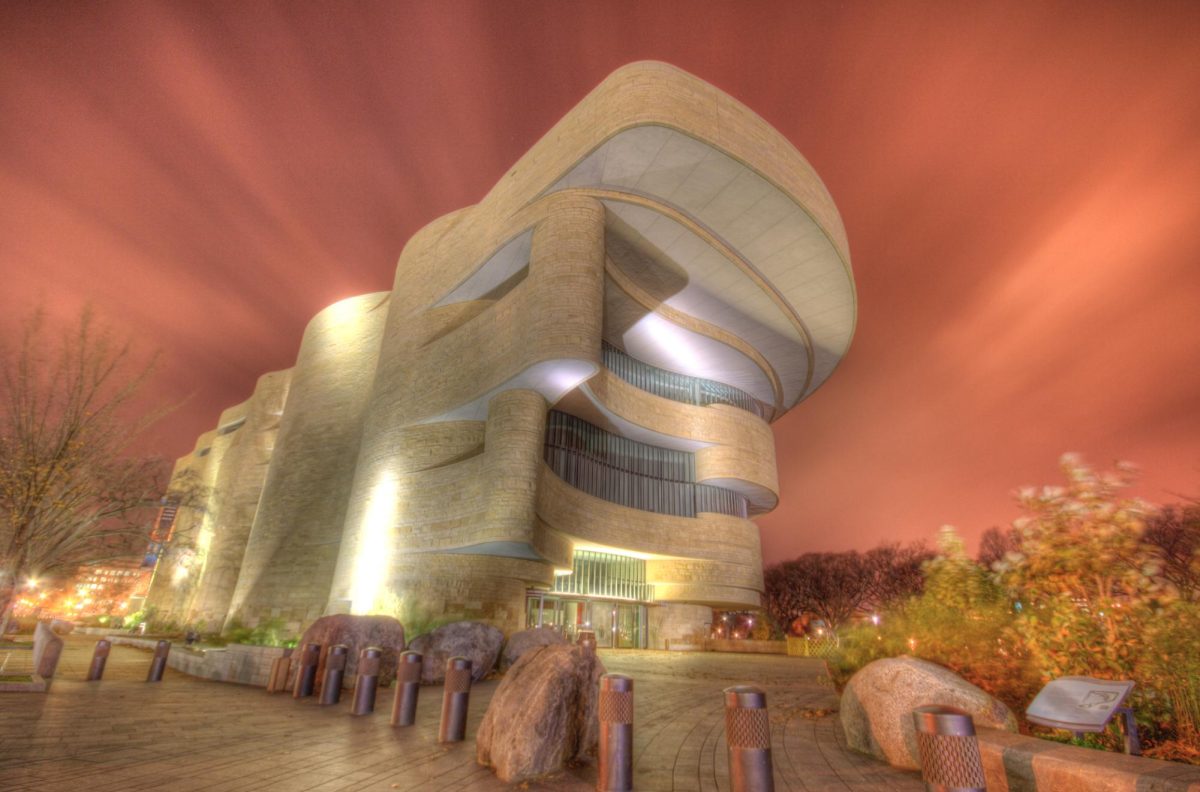

Throughout history, the portrayal of the American West in art, pop culture and media has been tainted by prejudiced ideologies and stereotypes. However, Smithsonian American Art Museum’s exhibition “Many Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea,” challenges this outlook and offers a broader and more diverse representation of American history.

Including work from 48 different artists in order to highlight perspectives of the various communities that define the West, the exhibition’s purpose is to confront the romanticism of America and represent the history, culture and artistic expression of marginalized groups who have often been erased in the Western narrative.

The exhibition is broken up into three sections: Caretakers, Memory Makers and Boundary Breakers. Together, these paint a more full picture of the diversity and complexity of America.

The show is made up of several forms of media, including paintings, sculptures and photography.

The opening section, Caretakers, reimagines what it means to take care of one’s land, community, language and culture in order to preserve the past history and leave legacies for those to come. Featured artists, such as Ka’ila Farrell-Smith, from the Klamath Modoc tribe, Awa Tsireh/Alfonso Roybal from the San Ildefonso Pueblo, Patrick Nagatani and Marie Watt from Seneca, demonstrate their commitment to the stewardship of the land and the honoring of traditions through art.

One displayed piece is Tirseh’s watercolor “Eagle Dancers,” which depicts a clash between the art traditions of the indigenous Pueblo peoples and contemporary modernist art styles that gained popularity in the early 20th century.

The second section, Memory Makers, shares the raw history of our country, bringing to light the neglected or erased stories that are essential to the narrative of the West. The artwork focuses on lived experiences and culturally important memories that have been passed down through generations. Artists Jacob Lawrence, Roger Shimomura, Christina Fernandez and Wendy Maruyama present a broader view of the American West.

This section includes perspectives of four Japanese American artists, drawing from aspects of World War II. Shimomura’s “American Infamy #2” is a reflection of his time spent in the Minidoka internment camp in the early 1940s. The painting contrasts vibrant families in the camp against a dark, looming figure and ashy black clouds covering the foreground.

Maruyama’s work also presents an account of the Minidoka internment camp. Her installation is made up of suspended sculptures that include 120,000 identification tags of Japanese Americans forced into incarceration.

The final section, Boundary Breakers, challenges the common story of the West and highlights identities and experiences that were previously misconceived. “These artists are speaking from a place they know well,” said museum coordinator Anne Hyland in an interview with Smithsonian Magazine.

Each art piece is based on lived experiences or stories passed down to the artists that contradict the romanticized notions of America. The artists include Angela Ellsworth, Raphael Montañez Ortiz, Wendy Red Star of the Apsáalooke/Crow nation and Angel Rodríguez-Díaz.

A notable piece in this section is Montañez Ortiz’s “Cowboy and ‘Indian’ Film,” which uses film director and stage actor Anthony Mann’s Western classic as raw material for his own work. Ortiz took snippets of “Winchester ’73” and recut them, completely rewriting the movie’s meaning as a retaliation against the traditional depictions of indigenous groups in the media.

The exhibition is on display from July 28 to Jan. 14 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington.